"Alice in Wonderland"

"Durer, portrait of man with bra"

"Beer Garden"

"Untitled"

Online Critical Writing Project for ArtH 385. An examination of the art scene in Los Angeles, this blog exists as a search for and review of artistic expression in the City of Angels.

Richard Avedon began his photography career in the realm of fashion, but his unconventional style of portraits combined with his ability to find interesting and captivating subjects created a niche for him in the consumer-driven art world. This current exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art presents a selection of work from his entire cannon, ranging from photos taken in the 1950s all the way to 2004, the year of his death. His work as a whole reveals the artist’s obsession with the human body (especially the face) as an aesthetized form. This review will address critiques of Avedon’s approach to photography and discuss whether he deserves a place within the realm of “high” art.

In Abigail Solomon Goddeau’s article “Art after Art Photography”, she notes that “the importance of photography within [postmodern art] is undeniable” and that post-modern photographers are successful because their “respective uses of the medium had less to do with its formal qualities per se than with the ways that photography, in its normative and ubiquitous uses, actually functions” (pg 2). Avedon’s work exhibits none of this critical analysis of methods of production, rather, he and his audience become engrossed with the subjects depicted in his work – here is an artist whose life work displays a fascination with persons and forms, not theories and experimental practices of art production. Because Avedon’s cannon exhibits a major emphasis on content, I will attempt to do an analysis of this alone in order to see whether or not Avedon is successful in producing anything other than glossy glam-art. If anything in the following three paragraphs sparks academic debate or conversation, then one must argue that Avedon’s work exists as something worthy of examination, even if he is not on the cutting edge of experimental practices.

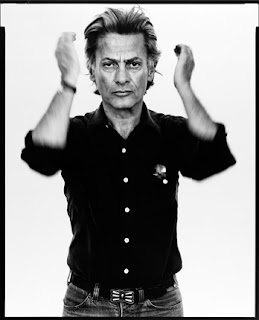

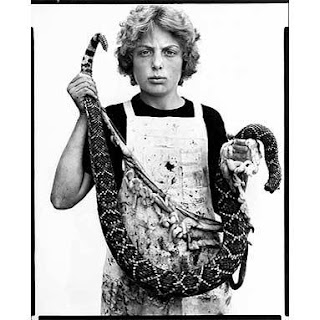

What makes Avedon's portraits stand out is the dynamic combination of the slick professional black and white film and a real candid approach to his subjects which allows for the piece to be viewed simultaneously as an artistic composition and an examination of character. MOMA made the excellent decision to include both his portraits of famous people (such as Marilyn Monroe, Bob Dylan, Bjork, and Janis Joplin, to name a few), as well as works from his book, "In the American West", in which Avedon traveled around the Western United States, photographing people in their place of employment. The two pieces from this collection featured below - entitled "Slaughterhouse worker on the kill floor

In this way, Avedon's work is highly utilitarian (if one were to ignore the glaring fact that he sells his pieces for a high price). For instance, the contemplative looks on the slaughterhouse worker and Bob Dylan are almost identical. Also, Avedon chose to shoot the slaughterhouse worker in his place of employment and Bob Dylan in

I see a similar connection between the two lower portraits as well. Aside from the fact that both subjects are blond, there is a definite compositional parallel between these two pieces. Both of these portraits are examinations of the intersection between individual identity and the identity one assumes upon entering the workplace. For

Therefore, Avedon's work as a whole exists as an interesting look into the human side of both celebrity and anonymity in American culture. The black and white film and candid introspective moments which he uses and captures serve as methods with which the artist can level the playing field, forcing the viewer to look at these portraits as an examination of character and humanity in relation to specific work and specific places. In this way, Avedon’s work encourages discussion of history and American life as it relates to people, their faces, and the places they work (as well as the work itself). Of course, one could simply walk by and become immersed in the image with no critical eye, but the possibility of meaning through the juxtaposition of these portraits still remains. Is Avedon a successful post-modern artist? No, because he makes no attempt to situate himself within the language of post-modernity, and makes no emphasis on the modes of production. However, this does not mean that his work has no potential for a critical reading other than a dismissive one.

d on briefly during the lecture. Both Cindy Sherman and Troy Brauntuch are famous for highlighting the process of photography and mechanical reproduction in their pieces, as well as suggesting a larger narrative which takes place outside of the photographic frame. However, the two artists go about it in two drastically different ways. Sherman highlights the cameras ability to imitate, augment, or re-contextualize an image or point of view by utilizing dramatic angles, heavy make-up, a shutter speed which closely approximates the medium of film (film plays at 24 frames a second, a

d on briefly during the lecture. Both Cindy Sherman and Troy Brauntuch are famous for highlighting the process of photography and mechanical reproduction in their pieces, as well as suggesting a larger narrative which takes place outside of the photographic frame. However, the two artists go about it in two drastically different ways. Sherman highlights the cameras ability to imitate, augment, or re-contextualize an image or point of view by utilizing dramatic angles, heavy make-up, a shutter speed which closely approximates the medium of film (film plays at 24 frames a second, a nd it appears that Cindy is shooting at around 1/15th of a second, which replicates the cinematic look), and back-lit projection, another common filmic trope. These images also suggest a larger narrative taking place; there is not a single one in which Sherman or her subject are looking directly at the camera lens. Instead, their eyeline goes away from

nd it appears that Cindy is shooting at around 1/15th of a second, which replicates the cinematic look), and back-lit projection, another common filmic trope. These images also suggest a larger narrative taking place; there is not a single one in which Sherman or her subject are looking directly at the camera lens. Instead, their eyeline goes away from

(detail)

(detail)